The 1970s: Class I, Splits, and Loci Differentiation

The 1970’s was all about class I, splits, and loci differentiation. Now that researchers had an idea of what they were working with, they were really getting into the swing of things.

The Nomenclature Report in 1970 was all about new specificities. Several new antigen specificities were identified and the Nomenclature Committee approved their addition to the list.1 However, researchers began noticing cross-reactivity of known specificities by 1972. The cross-reacting subtypes were added to the HLA nomenclature using the next available numbers in sequence and given a provisional ‘w’ as they worked out the validity of these reactions that eventually became known as ‘splits‘.

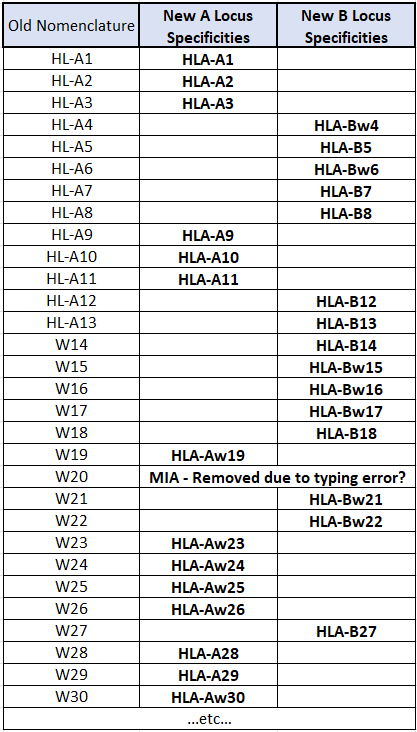

By 1975, a new breakthrough identified that the HL-A system wasn’t just one locus, it was multiple series of loci (A, B, C, D). Antigen specificities were officially categorized by genetic locus and the HL-A system was renamed to HLA in order to accommodate this.

Eventually, the HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C loci were grouped into Class I, with the new D reactivities transforming into a separate series of Class II loci (HLA-DR, HLA-DQ, HLA-DP) that expands during the 1980s.

What is the Purpose of the ‘w’ in HLA Specificity Nomenclature?

In the 1972 Nomenclature Report, during the discussion of splits, the Nomenclature Committee wanted to acknowledge the presence of new reactivity but decided to give each split ‘provisional acceptance’ while they worked out the relationship of the splits and any future antigens.2

The ‘w’ stood for ‘working’ or ‘workshop’ to indicate that it was only provisionally accepted but had been given an assigned number by the Committee. Once the specificity was officially accepted (gaining full status), the ‘w’ would be removed. That was the plan.

In the 1977 Nomenclature Report, the Committee was concerned about the possibility of confusing accepted C locus names with complement factors.4 C2 (an accepted HLA allele) is identically named to C2 (complement factor).

For this reason, HLA-C locus antigens were given a provisional name (Cw1) during investigation and once they were fully accepted, the name Cw1 stuck (keeping the ‘w’ and having full status simultaneously). This was not true for the A or B loci, which lost their ‘w’ once gaining full specificity status.

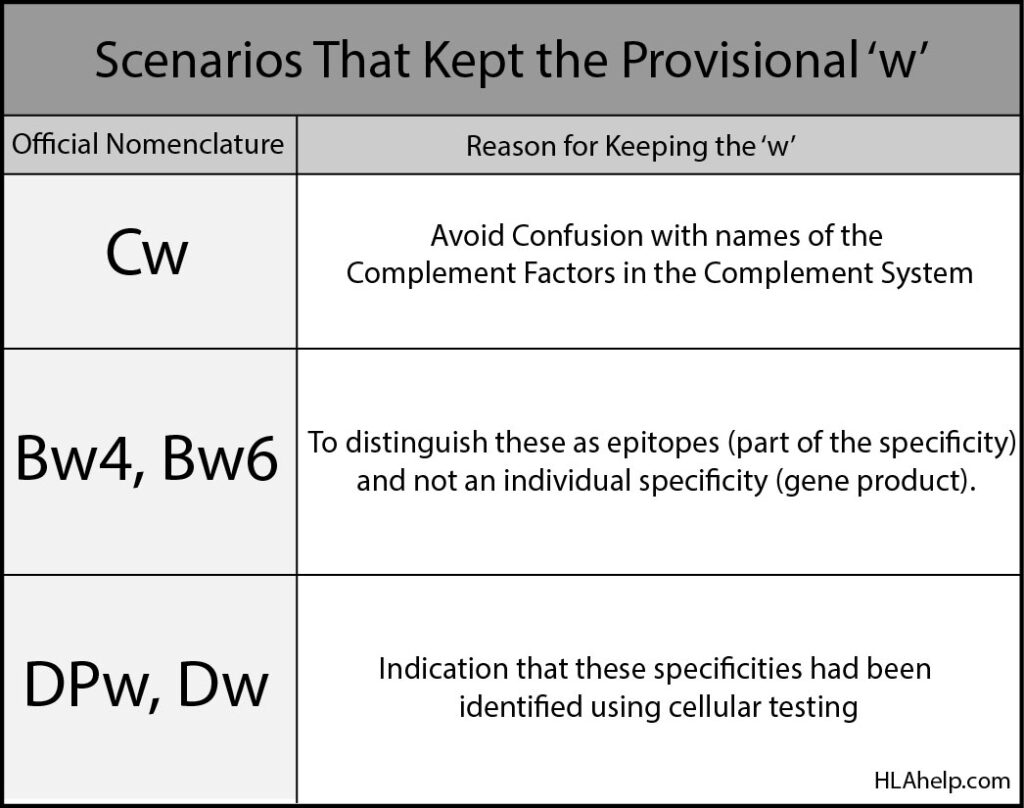

In the 1991 Nomenclature Report, the ‘w’ was to be maintained in a few other instances as well.5,6

- The C’s, which we just mentioned, kept their ‘w’ to avoid confusion with complement.

- Bw4 and Bw6 were working names that also became officially accepted nomenclature to distinguish them as epitopes rather than gene products.

- Finally, the ‘w’ was maintained for certain DPw and Dw antigen specificities to indicate that they had been identified by cellular testing.

By 1991, with the introduction of sequencing, serological types were only added officially to the record if they had a corresponding sequence, removing the need for any new provisionally-accepted ‘w’ specificities.6

The only ‘w’s that stayed as part of official HLA nomenclature were the Bw4/Bw6, Cw, Dw, and DPw.

What Are Splits? Notation Variety

Class I is full of parent antigen specificities and their associated subtypic splits.

But what are splits?

Here is an official way of defining HLA splits5:

“The subdivision of an original specificity through the subsequent discovery of newer, more specific reagents.”

HLA Beyond Tears (2nd Ed.) by Glenn Rodey

As the development of reagents for HLA specificities progressed, so did the ability to target increasingly discrete aspects of a specificity. Researchers were discovering that known antigen specificities (already approved and named by the Committee) were showing cross-reactivity. This was because they were targeting a more specific aspect of the antigen specificities.

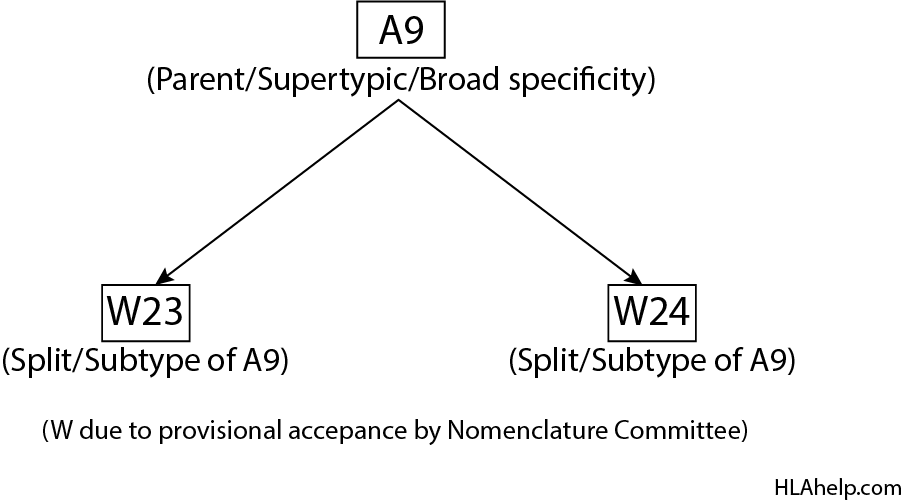

For example, the HL-A9 specificity was cross-reacting. This meant that cells identified as A9 were reacting with reagents that identify it as A9 (as expected), but A9 cells were also reacting to new reagents (unexpectedly). Because the reactivity was consistent, the Committee elected to give these split reactivities the next sequential numbers in the HLA naming convention. At the time of discussion and discovery, the numbers 23 and 24 were the next available numbers, thus W23 and W24 became the next specificities listed in the nomenclature. This means that A9 had reactivity that split further into W23 and W24. These splits are also known as ‘subtypic’ specificities, subgroups, or subpopulations.

A9 showed reactivity that split into the subtypes W23 and W24 (’W’ = working/workshop).

Because A9 had these subtypic specificities, A9 became known as a ‘parent’, ‘broad’, or ‘supertypic’ specificity.

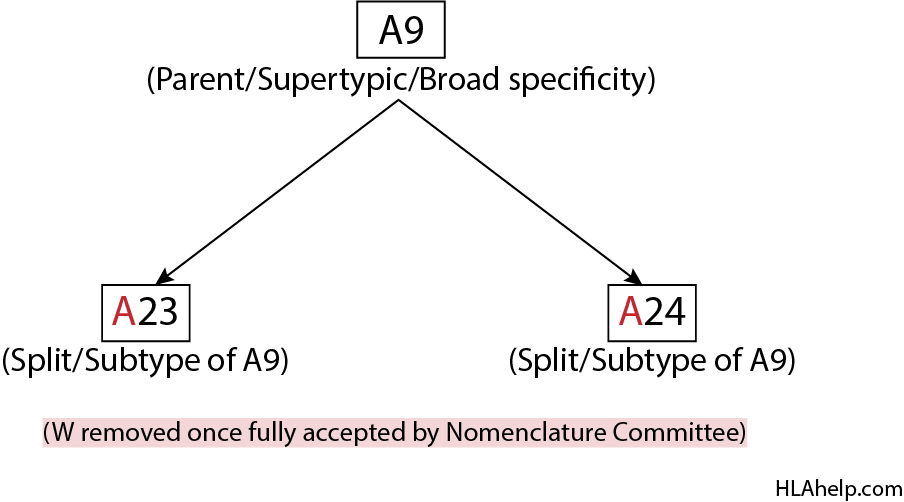

Once the subtypes were confirmed, they were given full status, which meant removing the W and replacing it with the ‘A’ designation. The numbers don’t change; those numbers are specific identifiers. What changes is our surety of them as an antigen specificity. (You can see the answer to the next question: “What is the Purpose of the ‘w’ in HLA Specificity Nomenclature” for more information).

What were the reagents detecting?

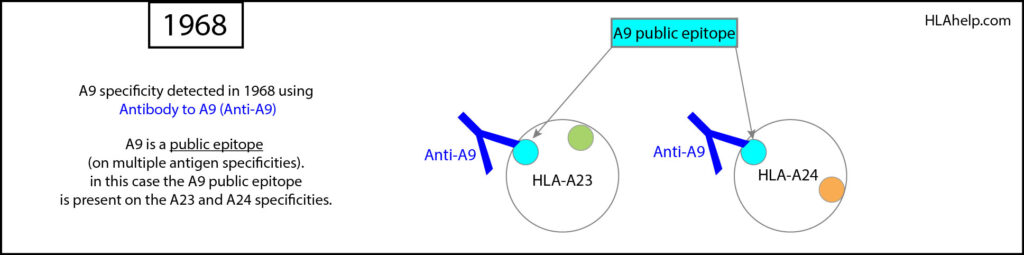

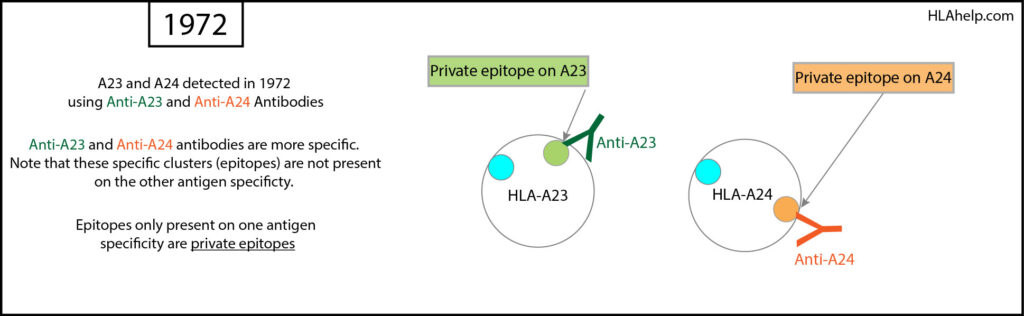

The reagents were detecting epitopes, which are clusters of amino acids situated closely together on the HLA molecule, creating a target for antibodies. The A9 antibody reagent was detecting the A9 public epitope. The A23 and A24 antibody reagents were detecting private epitopes.

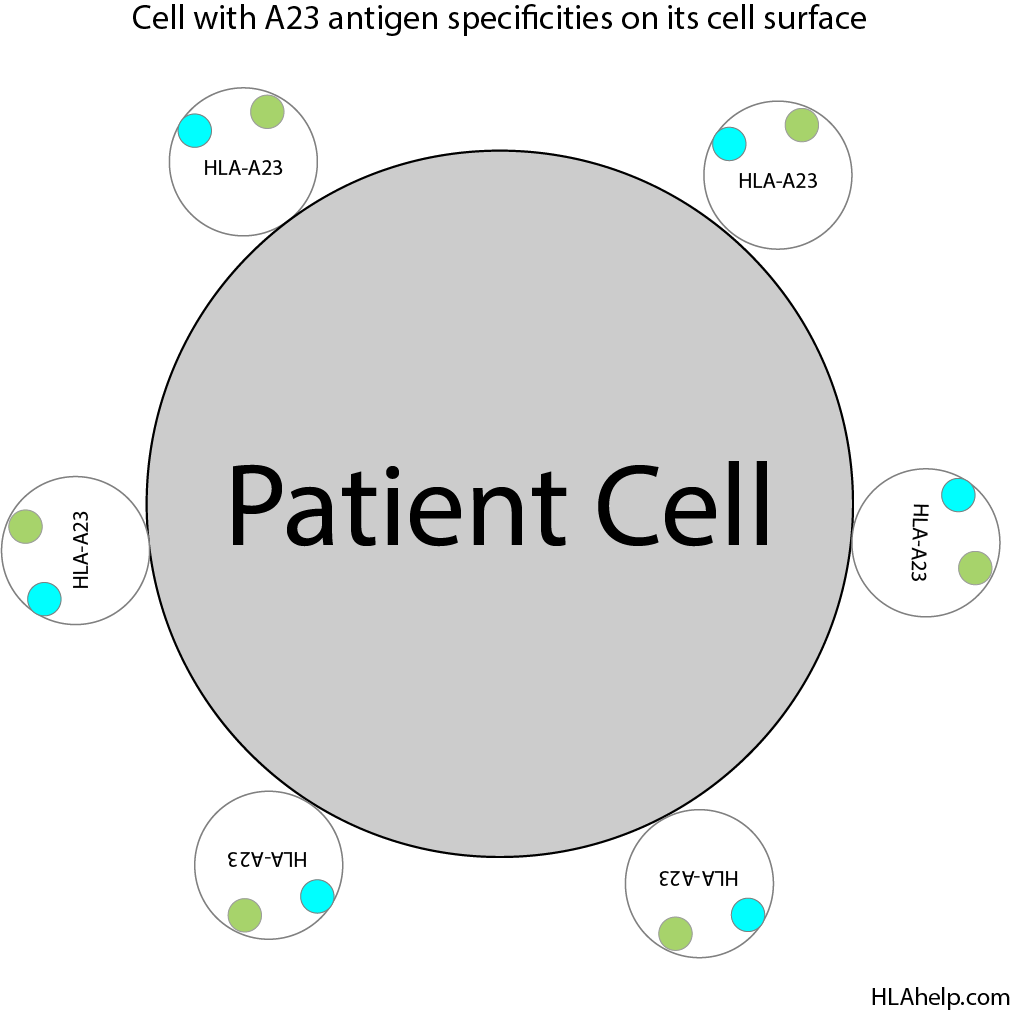

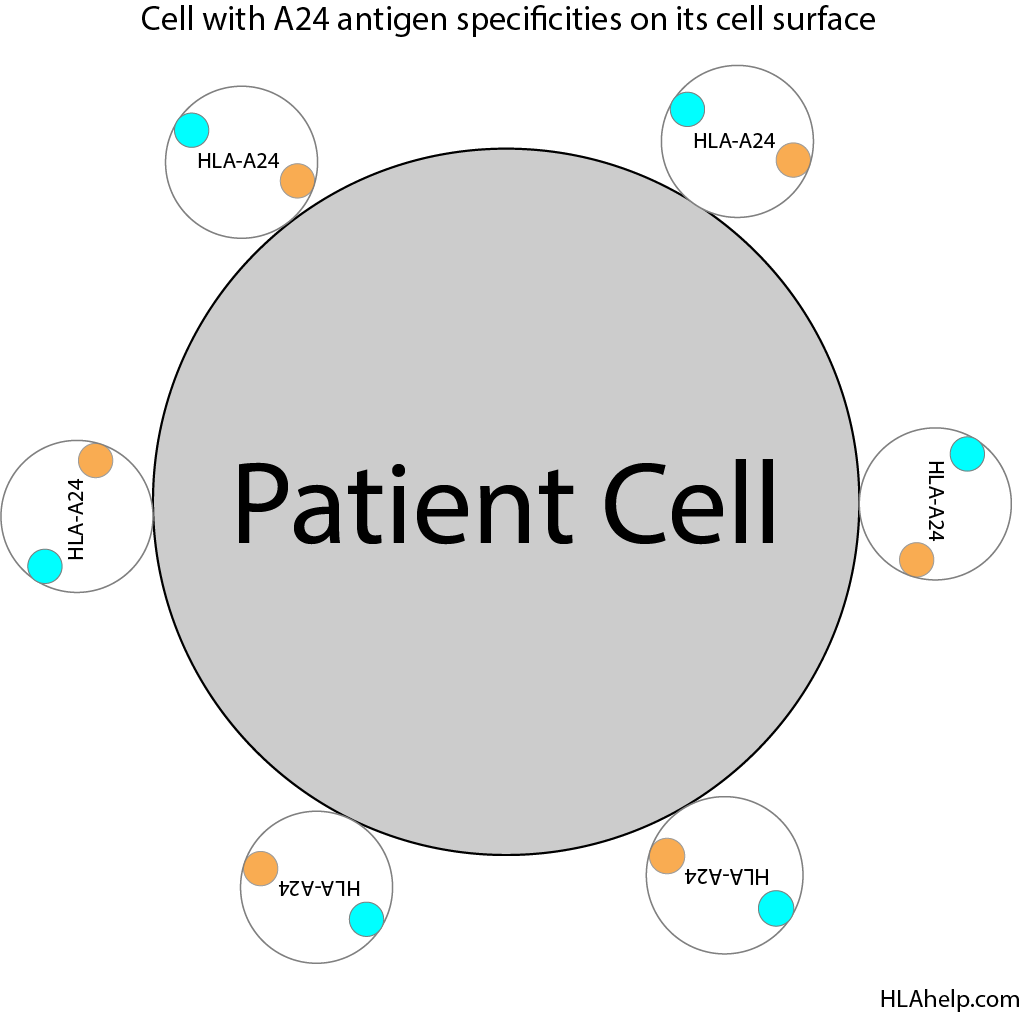

Here are two patient cells. One cell has A23 antigen specificities on its surface. The other has A24 antigen specificities on its surface. But you might notice that there’s the same cyan-colored spot on both A23 and A24 antigens.

Public epitopes are present on multiple different antigen specificities. In this case, the A9 epitope/amino acid cluster is present on both the A23 and A24 specificities. This is what the original A9 reagent was detecting.

Private epitopes are present on only one antigen specificity. There is a private epitope specific to A23 and a private epitope specific to A24 that help distinguish the two specificities. The more specific reagents allow the A9 cells to be further distinguished as either A23 or A24.

So how are splits notated?

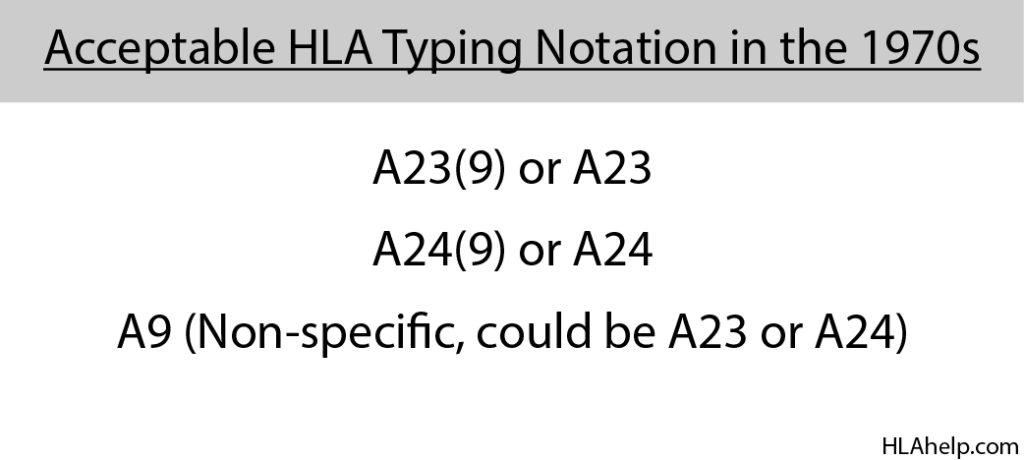

In current nomenclature, splits are sometimes marked with the parent specificity in parentheses. We now know that A9 splits into A23 and A24. This can be notated in official nomenclature as A23(9) or as A23. Similarly, A24(9) and A24 are referencing the same antigen specificity. One form identifies the parent of the split (A9) while the other does not. Both notations are acceptable. If a cell is typed as A9, this means that it could be an A23 or an A24 subtype. This type of result likely meant that the laboratory performing the typing didn’t have reagents available to clarify whether the A9 cells were more specifically A23 or A24.

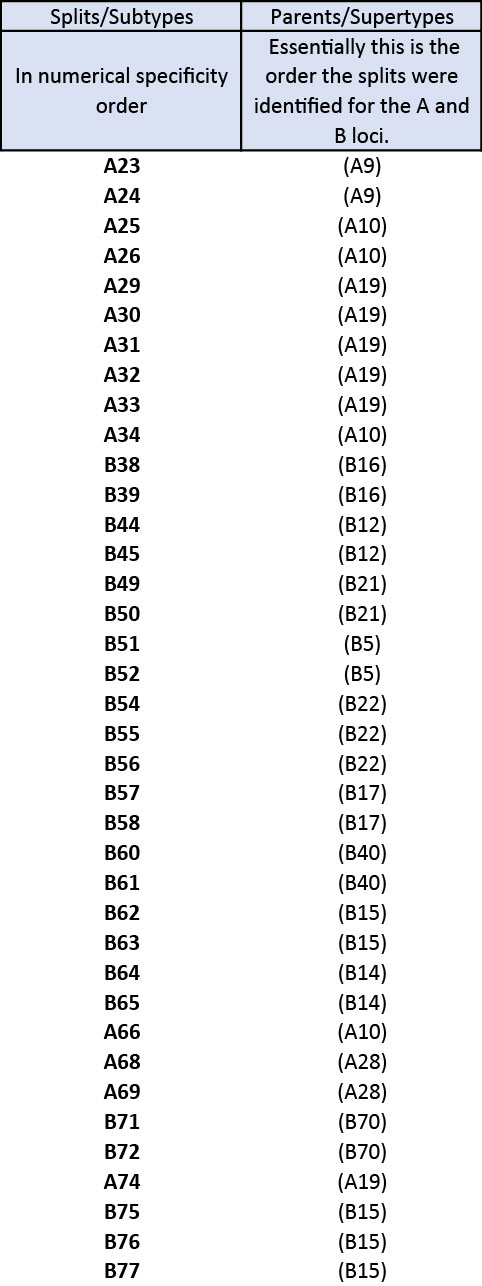

This method of giving splits the next numbers in the sequence as they’re discovered also explains why so many splits share a running number sequence (ex: A28 splitting into A68 and A69, B22 splitting into B54, B55, and B56, etc), though not all do. Interestingly, this also means you can identify the order the splits were encountered in the A and B loci when specificities are placed in numerical order, because the A and B locus were named as a single running sequence. In this case, A9 and A10 subtypes were the first identified, followed by A19, some more A10, and then B16 as we can see below. This was organized purely for fun and serves no other real purpose beyond curiosity.

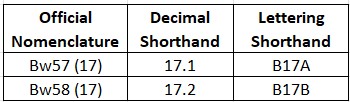

Some shorthand nomenclature methods were also used to identify subtypes/splits, though these are unofficial names. Some easy examples are present with the B17 that split into Bw57 and Bw58. There were a few different alternative shorthand naming methods. For example:

Decimal points followed by a number sequence

B17.1 for Bw57

B17.2 for Bw58

Lettering shorthand

B17A for Bw57

B17B for Bw58

There are also ‘long’ and ‘short’ designations that will be discussed more in the 1990’s.

You’ll see these shorthand versions in historical HLA articles but this is not common practice today.

The W’s, however, they stuck.

But what are the ‘W’s doing there?

So When Did HL-A Become HLA?

In 1975 the Nomenclature Committee wanted to simplify the notation as they began recognizing how large the HLA system was.

“…The hyphen previously used in the designation of the HLA system is being dropped in order to minimize the increasing number of symbols needed to define loci and specificities belonging to the system.”3

HL-A became HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, etc. HL-A nomenclature assumed only one locus. The “HLA” prefix allowed them to split the HL-A specificities into HLA-A and HLA-B without needing to rename or reorganize specificities (See ‘Why are the A locus and B locus numbers so confusing?’ for an example of the updated nomenclature). This “HLA” prefix also distinguishes the locus letter, allowing it to act as an essential part of the specificity’s notation and includes space to account for future developments.3

Specificities were to be numbered sequentially (beginning with 1) for each locus (except A and B, which were named jointly). This meant the locus letter was a critical part of the name and needed to be clearly distinguishable (ie: the specificity ‘1’ is useless without knowing the locus letter. Is it A1? C1? D1?).

Why are the A Locus and B Locus Numbers So Confusing?

All the other loci are sequential (as much as they can be, lol). But why don’t A and B loci have their own sequences, each beginning with 1?

This is another example of “we didn’t know how big this was gonna get (or what we were working with)”. Totally fair. You don’t know until you know.

The first specificities discovered in the 60’s were named in sequential order as they were discovered and verified. By the time researchers realized they had two clearly distinct loci (A and B) they were in the process of discovering C locus specificities. This means the C locus was discovered just in time to be named with sequential numbers (beginning with 1), as were the Class II loci that came later, but the A and B loci sequences were already tangled between each other.

To maintain the status quo, the Nomenclature Committee decided to continue naming the A locus and B locus jointly (using the same combined numerical sequence), while all future loci started their own numerical sequences at 1.3

Nomenclature Report Summaries Through the 1970s

The A, B, and C loci were established. The two systems previously identified in the 1960s became the HLA-A locus (LA system) and the HLA-B locus (FOUR system), with 4a becoming Bw4 and 4b becoming Bw6.3 (Bw4 and Bw6 are common public epitopes for the B locus)

While the 1970’s were about HLA Class I (loci A, B, and C), scientific advancements in the 1980’s focused research on the HLA Class II specificities (the D’s).

References

- WHO Nomenclature Committee (1970). WHO terminology report, 1970. Histocompatibility Testing (1970), 49. https://hla.alleles.org/inc/images/WHO_Terminology_Report_1970.pdf

- WHO Nomenclature Committee (1972). WHO terminology report, 1972. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 47, pp. 659-62. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2480838/pdf/bullwho00185-0117.pdf

- WHO IUIS-Terminology Committee (1975). Nomenclature for factors of the HLA System, 1975. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 52, pp. 261-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2366374/pdf/bullwho00465-0026.pdf

- Albert, E., Amos, D.B., Bodmer, W.F., Ceppellini, R., Dausset, J., Kissmeyer-Nielsen, F., Mayr, W., Payne, R., Rood, J.J., Terasaki, P.I., Trnka, Z., & Walford, R.L. (1978). Nomenclature for factors of the HLA System, 1977. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 56, pp. 461-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2395588/pdf/bullwho00440-0129.pdf

- Rodey, G.E. (2000). HLA Beyond Tears: Introduction to Human Histocompatibility (2nd Ed.). De Novo, Inc. ISBN: 0-9678268-0-2

- Bodmer, J.G., Marsh, S.G.E., Albert, E.D., Bodmer, W.F., Dupont, B., Erlich, H.A., Mach, B., Mayr, W.R., Parham, P., Sasazuki, T., Schreuder, G.M.Th., Strominger, J.L., Svejgaard, A., & Terasaki, P.I. (1992). Nomenclature for factors of the HLA system, 1991. Tissue Antigens, 39, pp. 161-73. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1399-0039.1992.tb01932.x

- You can find a link to all relevant nomenclature reports at https://hla.alleles.org/nomenclature/nomenc_reports.html

One Response